On Saturday, Amy and I spend the day at St. Mark’s Methodist Church attending a workshop on early childhood education. Along with Tom Hunter and Michael Leeman, Bev Bos sang some songs, told some stories, and evangelized about a better way to engage young children in learning.

There is a tremendous amount of material to absorb and process. The content pertains to our adventures in educating Carter, of course, but it also is relevant to my own explorations as a college professor wannabe. It is also relevant to interaction design, both in the practice and philosophy of human-centered inquiry. Although blog posts are likely to follow on these insights, I am going to start by focusing on the two biggest take-home messages of the day:

- Play is not a luxury.

- We don’t change because we’re under a spell.

Bos has compiled a number of resources to inspire the creation of playful learning spaces and a child-centered approach to education, much of which revolves around these two ideas.

Play is not a luxury

A big name in this field herself, Bos dropped two other names in explaining the importance of play in education. David Elkind is a professor at Tufts Univeristy specializing in child development. Elkind, who also has some very interesting things to say on the impact of technology on growth, believes that there is a decline in social markers caused in large part by the trend for schools to “push down” curriculum from upper elementary into the early education of our youngest students. Jean Piaget is a key developmental psychologist who defined four stages of childhood development. The second one—Preoperational (ages 2-7)—is the one Bev Bos sees with her own school.

“Play is not a luxury but rather a crucial dynamic of healthy physical, intellectual, and social-emotional development at all age levels.” (David Elkind)

“Play is the answer to the question—How does anything new ever come about?” (Jean Piaget)

Unfortunately, play is being treated as a luxury from the moment a child reaches school age. One of more discouraging revelations about the changes to public education in the past thirty years is that there recess, if it exists at all, is down to 20 minutes of rules-constrained interaction. Heaven forbid it rains, or even that scrap is tossed in the form of a Magic School Bus video. This shift is one of the ideas pushed down from above. Across cultures, play is seen as an antithesis to work—the thing you do when you aren’t being productive, when you are relaxing, when you are not serious. Since we keep trying to prepare children for that mindset earlier and earlier, play even gets that rap in elementary and pre-schools.

There are two big problems here. First, we learn through play. Bos claims that 98% of the information children receive leaves our brains in five minutes unless it is (1) real, (2) hooked to an emotion, and (3) relevant to that child. Play is tangible. It is a way to make mistakes that create experiences without lasting consequences. Even when the genre is science fiction or other fantasy, play is about the real. It is passionate, sometimes quietly so, and it is always relevant to the participants (unless someone was coerced into the activity).

Second, we are built to be lifelong learners. And if we learn through play, it makes sense that our education and motivation to innovate is tied not to work—that serious, extrinsically motivated commitment—but to play. It is thankfully more and more common to find IT company policies that encourage games and personal projects, recognizing the long-term benefit to the business in the form of attitude, loyalty and idea generation. Kosmix, for example, has a frequently-used ping-pong table and foosball tournaments. Icosystem, a Boston-based complex systems consultancy, has a big open space at the center of a ring of offices with one section devoted to legos and other toys. Play stimulates the mind.

This is especially true of design. The techniques we use to learn about a user group before and brainstorm new concepts before we build owe much to the idea of play. Yet human-computer interaction also perpetuates that same stigma, where work is serious and play is not. That comes from the scientific method and tradition of legitimacy in hard science to which HCI aspires. GOMS is work. Comicboarding is play. Both can still be serious.

We’re under a spell

Bos quoted a Stanford professor who once answered the question of why we don’t change, saying we’re under a spell. What will allow us to change is to find a stronger spell.

In other words, we tend to do things out of fear and habit. Even if we don’t like the way some of the world works, we know that if we do certain things we can game that system and get by all right. Our schools are the cheat codes. We fear the unknown, so any change—especially seemingly radical or counterintuitive ones—is something to be avoided. We accept these limitations too easily because we have the spell of our own experiences, of media reinforcement, and power differentials.

When we parent (or educate, or design), there are several spells in the ether. There is always a master spell cast over the culture, inherited from generation to generation. There is also our personal spells constraining our teaching. The more tired I get, the less patience I have for delay and the more I find myself parroting the phrases and attitude of my own parents. The third and most potent spell being cast is the one forming around the child, based on their own new experience with the world. The stronger our spell, the stronger his spell.

In design, we see this in the form of job approval, the bottom line, and technology-centered iteration. There are all of these forces nervously and constantly informing us that we have to get done quickly and not good development time conducting design inquiry. Upon leaving the IU School of Informatics, we young HCI-ers are urged to find our voices and our resolve early in our careers and help change the culture. Through good design work, we are breaking the spells constraining our interest.

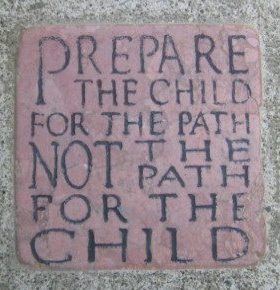

Image from Pathways to Learning

4 replies on “Play is not a luxury”

Our schools are the cheat codes. We fear the unknown, so any change—especially seemingly radical or counterintuitive ones—is something to be avoided. We accept these limitations too easily because we have the spell of our own … Continue readinghere.

I love this post Kevin, such a good reminder for Vanessa and I especially since we have younger kids in the house. You have started to draw analogies into HCI already and bringing play into the workplace. Of course Google has a number of playful, and outright fun policies, and well as a number of forward thinking companies as you mentioned, we need to encourage these kinds of policies within the SOI, and in our various workplaces as we go out. In making cases like this however, we will need reasoning and proof (so to speak) and some of the things you referenced are a good beginning.

All of this is is good for people’s stress levels, their creativity, and sense of well-being.

So can one be scientific and fun? can you play science and still get serious results?

I know you can make design fun, and still get great results.

Very, very familiar…..read a biography of JJ Rousseau a few months back. He was able to articulate much of this in 1762. But then again, he probably wasn’t the first either….

http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-rous.htm#education

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Jacques_Rousseau#Education

On the perhaps more extreme side, he thought that reading ‘early’ is not such a good thing, fearing absorption over learning. Perhaps this view would now be ameliorated by a greater choice of books.

Celeste went to this. My work wanted to send me, but I decided not to go since I work primarily with families as opposed to just children.

Glad to see it was informative.