My journey into the community of practicing smartphone aficionados began in earnest today when I unboxed my new Android G1, courtesy Hanapin Marketing. Before that moment, I had held one other Android in my hand, borrowed from an early adopting friend. Then and now, it surprises me how small it is.

I gravitated toward things with which I was most familiar—a phone call, web browsing, Twitter apps. Today’s reflection is about my exposure to the new interactions that came with the phone.

I started a blog thread on Smaller Indiana asking how important your cell phone has become to your day-to-day routine. There is also a short survey about cell phone functions you can complete. If you want to help me out, leaving feedback in any of these forums is appreciated.

Out of the Box

I know this thing is more than just a phone. I got four cables with it in the box to give it computer cred. Even though Hanapin did get a real T-Mobile phone service package with the phone—which incredibly arrived about 20 hours after making the online purchase—I was expecting some kind of activation process, or at the very least a lengthy battery charge. To my surprise, the manual suggested I try the little red power button. Moments later, the Android was squeaking at me.

My first hiccup, though, came quickly: with the login for my Google account. There were only two simple boxes on the screen, plus a displayed button (as opposed to the form factor ones on the device). It didn’t take that long to successfully click on the first one and type my username. Selecting the password field, however, was a challenge for me. The phone alternated between dragging the visible page up and down and briefly highlighting one of the two input boxes. With some patience and better aim, I got the cursor into the proper position to type. My password, though, wouldn’t take. I probably spent a good 5-10 minutes on that one first interaction before I could move forward.

Those two particular interaction issues—an inability to select objects on the screen, and difficulty getting my passwords to take—plagued me as I downloaded and explored a variety of applications.

My most important application is likely going to be the one that gets me access to Twitter. The tool of choice was Twindroid, a third-party Twitter application for the Android that was recommended on a number of sites. After surfing to the web site through a Google search, I clicked download (nothing happened) only to later read that installation required downloading software through the Android Marketplace, a button buried in a hidden window from the home screen. The process of locating and installing Twindroid was quick and easy, but I couldn’t get the application to accept my password. Giving up, I came back to discover it did, indeed, know who I was.

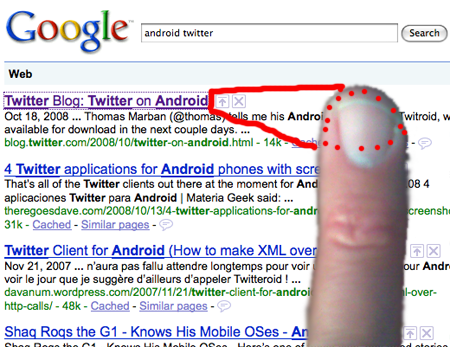

My index finger is huge compared to the links it needs to click

Re-learning Interaction

I’m not certain if this is a breakdown of feedback or expectation. Maybe I have to get used to unpredictability of so many coordinated connections (me, my phone, the data access service, the application, Twitter), where there may be more opportunities for a broken channel. I do know that it was very frustrating for me to not understand why the thing I wanted to do (log into Twitter through Twindroid) wasn’t working. Even with interactions I assumed I knew, there appears to be a separate learning curve unique to the smartphone environment.

This is particularly true with something as simple as clicking on a link or button. Unless the web site or phone application maintains the proportions of the target to the real-world size of the fingers touching them, the interaction creates a barrier to use and efficiency.

So far, I have encountered the following kinds of interactions:

- Click the Button—This is the most certain interaction, since it involves tactile feedback and some permanence of function. I’ve always got a way to get back to the main menu and navigate backwards in the current breadcrumb, but there doesn’t appear to be a way to move forward. In addition to the five buttons on the front, there are also two side buttons. One controls the volume, and the other takes pictures. I don’t know yet if they serve other purposes.

- Touch the Screen—I am not used to touch screens, but my expectation is that it is pressure sensitive, like the old kiosks where you have to push to make contact between lower layers under the surface. This is not how the Android touchscreen functions. A light touch is sufficient. In fact, I suspect the pressure I was applying after I first turned it on probably helped spread out my heat signature and made my fingers fatter.

- Tap the Screen—The first light touch seems to select. Holding down my finger or tapping a selected item appears to click it. Initially, there was a lot of combination interactions trying to force a response. As I have started using Twindroid and Google searches on the phone, though, a lighter touch and tap is giving me more control, and confidence.

- Drag the Screen—This is a basic but sexy interaction, where you can flick your finger and have the screen fly by in a multi-dimensional scrolling action. It is the same kind of interaction I would have with a piece of paper, so this was the easiest to get the hang of. The only drawback is when I mess up on the touch selection above.

- Turn the Screen and Slide the Screen—With the iPhone, you can turn the phone and it will detect orientation. While the Android has an accelerometer to potentially have this same response, the orientation of the screen seems to be tied not to the orientation of the device but whether or not the screen is slid open to reveal the QWERTY keyboard. It is nice to have the option of how to best view content, as well as having that content adapt to the change in screen orientation. However, sliding the screen out is an extraneous interaction unless you want access to the keyword. Similarly, it would be nice to be able to do some kind of typing without revealing the full keyboard.

- Typing—For someone who texts at the pace of an arthritic grandmother, I welcome more options afforded a QWERTY keyboard. I found myself typing with my right index finger to try to solve my password entry problems, but in general feel quite comfortable now using my thumbs to hunt and peck. The shift and tab-to-select actions, though, are awkward and non-existent, respectively. At some point, I’m going to compose a blog on the Android to really put it through the paces.

- Scroll the Selector—Initially, I found the little scroll wheel on the front of the device meaningless. I never used such interaction objects on laptops or mice that had them, so I assumed I would ignore it. It turns out that scrolling ball is very useful for navigating the links and form objects on web pages. It always retains context of what is visible on the screen, even if you scroll from the top to the bottom of the page quickly with the finger drag interaction. It may help solve my fat finger problem trying to hit the small text links.

- Shake the Phone—I’ve seen the iBeer app on video and other mindless apps that use the accelerometer to sense motion. The first (and maybe only) application I downloaded and installed that relies on this interaction is the Magic 8 ball. I shake the phone, the picture on the screen shakes as well. I am wondering how much shaking interactions will be used in meaningful applications (for example, if I start playing music, can I shake up the playlist to scramble it).

- Plug in the USB cord—This doesn’t help with my interaction on the screen, of course, but it was one of the first interactions I performed on my Android in order to keep it powered up. The phone comes with two USB connections, one that goes to an outlet and another that goes to a laptop.

Nothing life changing yet, but I have yet to try to integrate my phone into my daily routine.